Vol. 2, No. 2

How the Fed is engulfing the MBS market; The cost of capital; Credit creation • Cause & effect; The impact of rising rates on tech valuations; An undervalued U.S. retailer

Valuabl is an independent, value-oriented journal of financial markets. Delivered fortnightly, Valuabl helps contrarians pop bubbles, buy low, and sell high.

In today’s issue

House of the rising Fed (8 minutes)

Cost of capital (2 minutes)

Credit creation • Cause & effect (5 minutes)

Long-shots, not long duration (5 minutes)

Investment ideas (7 minutes)

1/ House of the rising Fed

Since the U.S. Federal Reserve (“Fed”) first announced and implemented its quantitative easing (“QE”) programme in March 2009, economists and pundits alike have hotly debated its effects on financial markets. Specifically, the conversation has focused on the Fed’s ability to control the monetary supply, inflation, and interest rates.

Before the global financial crisis (“GFC”), the Fed was, rightfully so, a substantial buyer of U.S. Treasury securities. Purchasing these financial assets helped monetise the national debt, prevent fiscal cliffs, and ensure the government always met its obligations. In fact, the U.S. Government’s ability to create money through the Fed, alongside that currency’s global reserve status, is a determining factor in the Federal Government’s favourable AAA credit rating—if Uncle Sam can’t pay you from his tax revenues, he can always borrow the money to do so from the Fed.

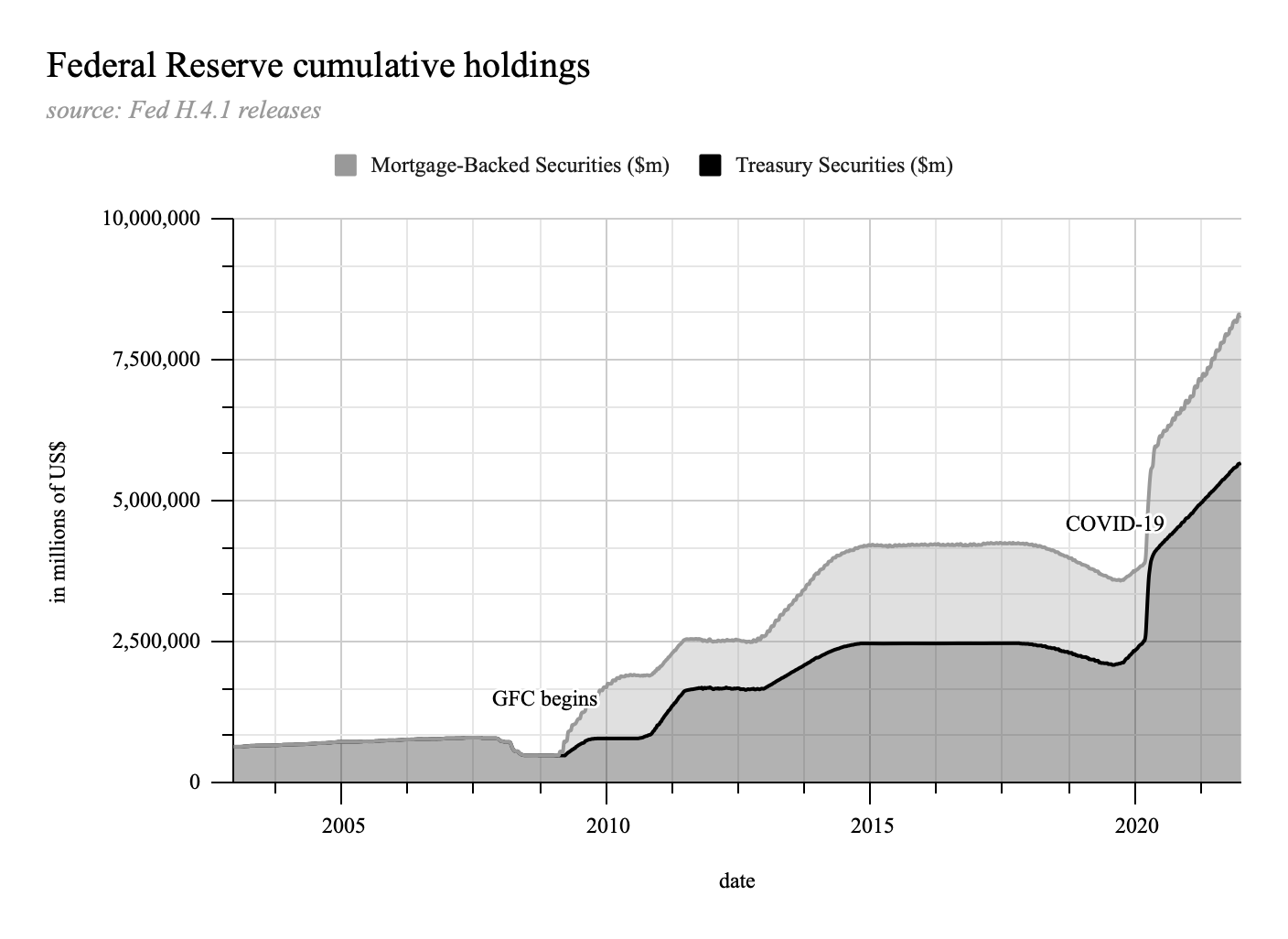

The Fed’s balance sheet was relatively tiny back in the good old money-actually-earns-interest days. To provide some perspective on this somewhat oxymoronic statement, in May 2007, the total value of all assets on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet was $894.6 billion1. Of course, this number already seems obscene to those of us who don’t meet at 2051 Constitution Ave., but relative to the leviathan the Fed has become, it is teeny. Since introducing quantitative easing, and as of the 13th day of this month, the Fed’s balance sheet has grown to $8,788.3 billion2—nearly 10x the size it was back in 2007. In 15 years, the Fed acquired almost $8 trillion worth of financial assets.

I doubt that the enormity of this number needs emphasising. Still, for that amount of money, and at current prices, you could buy: all the farmland in the U.S. for $2.7 trillion, Apple Inc. for $2.9 trillion, Saudi Aramco for $1.9 trillion, and JPMorgan Chase & Co. for $500 billion. So, what did the Fed buy? Well, the vast vast majority of assets they acquired are U.S. Treasury securities, including bills, nominal notes and bonds, inflation-indexed notes and bonds, and mortgage-backed securities (“MBS”). I’m probably being quixotic, but I’d prefer the former acquisitions to the latter.

Despite threats of quantitative tightening (“QT”)—that is, selling rather than buying financial assets—over the last 15 years, the Fed has been unable to follow through on this in any meaningful way. I concede that they did begin to tighten their belts in 2018, but it didn’t last long, and it seems clear that the Federal Reserve has fallen victim to Parkinson’s law3 and are spending at an exponentially increasing rate of +26% p.a.

Still, none of this is likely to be new to you. The financial press has well covered the neverending balance sheet expansion. But, what has been less covered is how effective or ineffective QE has been at achieving the programme’s stated and implied goals. As the layman understands, there are three primary purposes of the programme: 1) to increase the money supply, 2) to encourage lending and investment, and 3) to reduce interest rates. The first two have clearly worked. The money supply has gone from $8.4 trillion in March 2009 to over $21.6 trillion4; while, as I’ve covered in previous issues, public5 and private6 debt levels have increased dramatically, too. However, while the prevailing narrative is that the Fed’s involvement in buying Treasuries has suppressed U.S. government bond yields, I contend that its impact on this is less pronounced than many think.

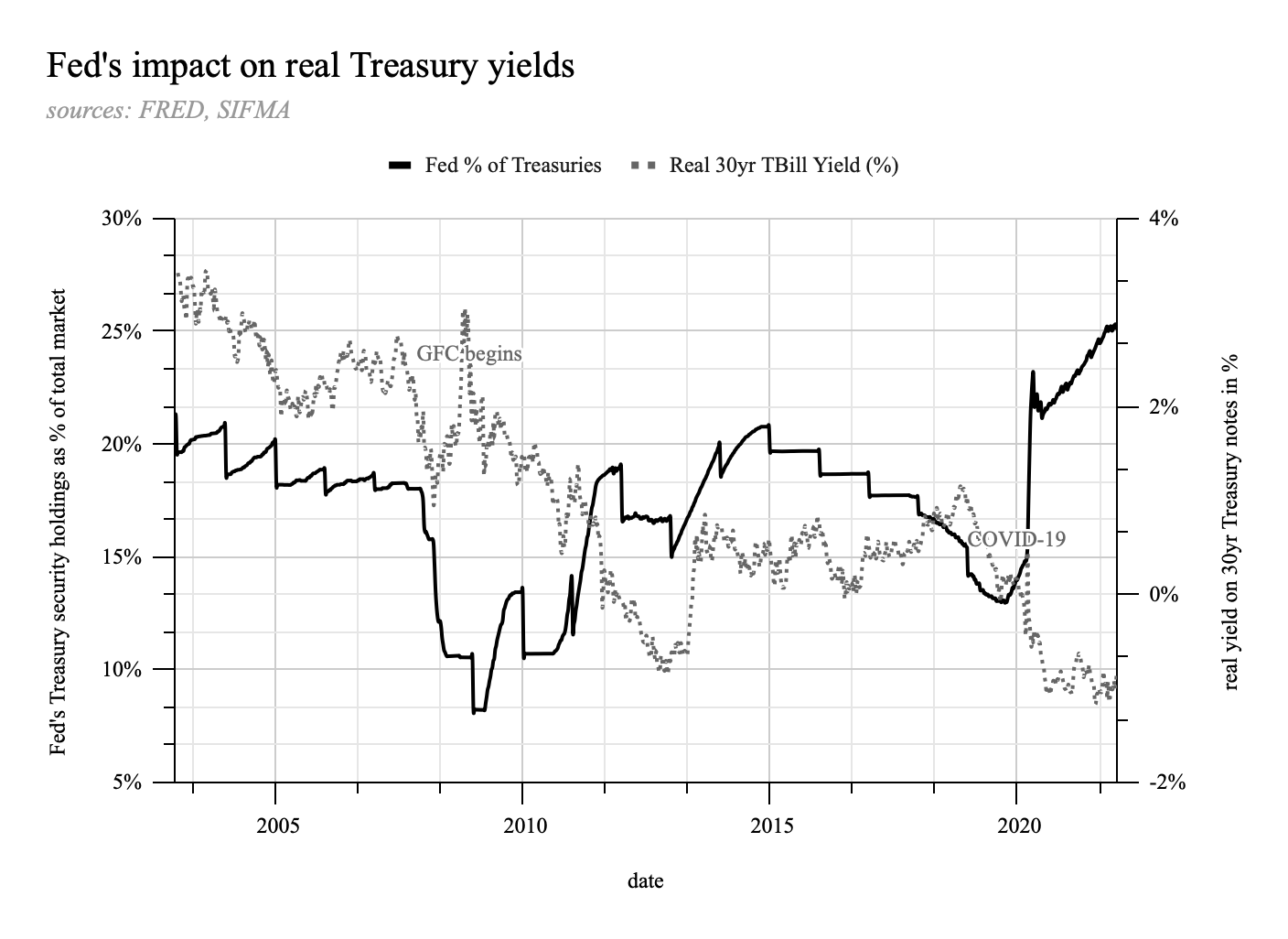

I plot the Fed’s holding of U.S. Treasury securities as a percentage of all outstanding ones alongside the real 30-year Treasury bill yield below.

A couple of things immediately pop out from this chart. The first is that real yields have been trending downwards—no big surprises there. The second is that during crises, the Fed’s involvement in the Treasury market has directly impacted real yields. During the GFC, yields declined as the Fed increased its role in the Treasury market. Again, the Fed’s exaggerated intervention in the Treasury market reversed the spike in real yields at the onset of the COVID crisis. On the other hand, during non-crisis periods, the Federal Reserve effect seems to be more subtle. These two samples have a slightly negative yet significant correlation of -0.20 (p<0.01).

Despite its balance sheet's enormous size and exponential growth, the Fed’s twenty-year relative trajectory as a player in the Treasury market is cyclical and flat. While the Fed’s buying programme has affected real yields, the argument that it is the primary reason for their decline falls flat when set against this data. There are many other buyers of Treasuries, including individuals, mutual funds, banking institutions, insurance companies, state and local governments, foreign governments, and pension funds. With many other entities buying these securities and the low but significant correlation with real yields, there is more to these low long-term yields than just QE.

However, the Fed didn’t spend all $8 trillion on Treasuries; it bought mortgage-back securities, too. Indeed, the Fed has gone from a total non-player in the MBS market to a dominant force with more than 22% of all outstanding U.S. mortgage-backed securities.

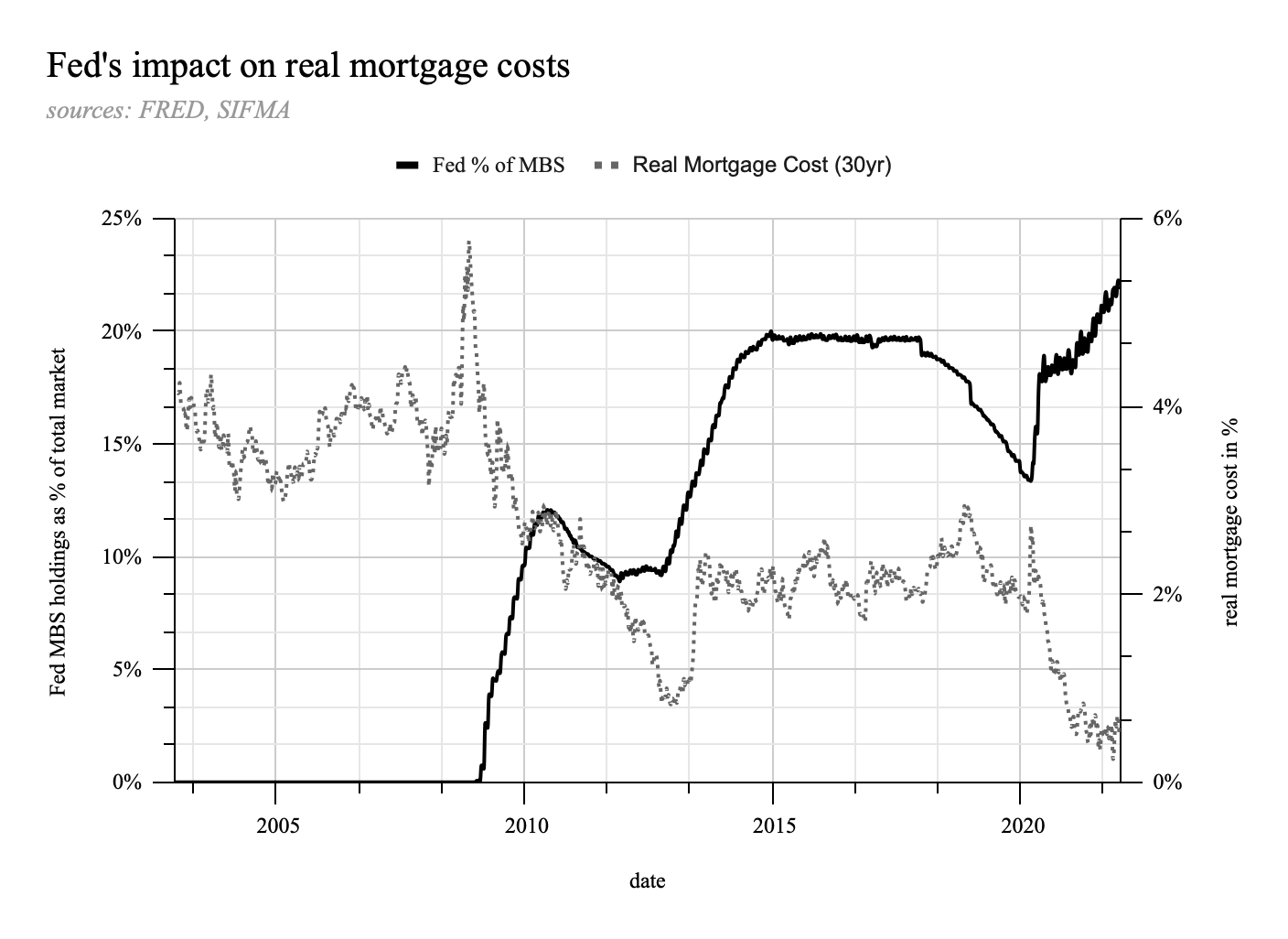

I plot the Fed’s holding of mortgage-backed securities as a percentage of all outstanding ones alongside the real 30-year fixed mortgage cost below.

The relationship here is much more pronounced than with Treasuries. These two series have a sizable negative correlation of -0.80 (p<0.01). So, why on earth is the Fed buying private securities?

During the fallout from the GFC, as mortgage credit dried up, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—government-sponsored enterprises (“GSE”) who bought and packaged mortgages to create, guarantee and sell mortgage-backed securities—still had $5 trillion worth of these securities and debts outstanding but were unable to make payments as an increasing proportion of mortgages were in default. The government, through the Treasury, stepped in and put Fannie and Freddie into a federal conservatorship to underwrite their obligations in an attempt to bring stability back to the mortgage market. As homeowners couldn’t pay their mortgages, Fannie and Freddie couldn’t make the payments on the MBS agreements they had outstanding to investors, which, in turn, meant that liquidity dried up and yields rose. The down-chain effect was: banks didn’t want to lend, Fannie and Freddie weren’t buying, and investors weren’t interested anymore. To signal confidence and inject liquidity, the Fed began purchasing these securities. However, they’ve never been able to offload them in any substantial quantity sustainably.

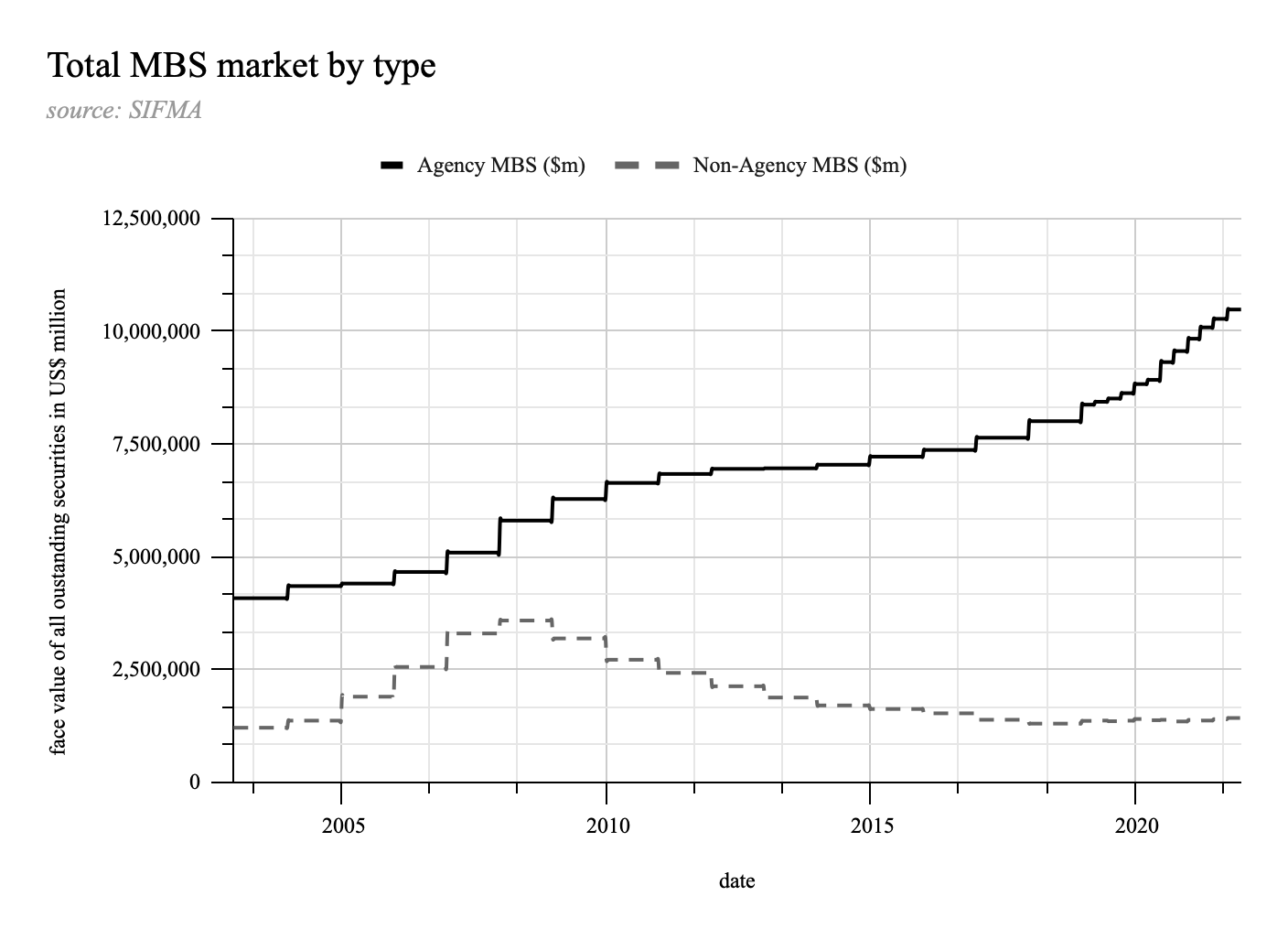

Every downturn in the economy has necessitated the Fed stepping in to buy these assets lest liquidity drain away and real mortgage costs rise, squeezing historically incredibly indebted households. Indeed, low mortgage rates and rising prices sound like a good thing? Not so fast, fella. Like the monkey’s paw7, these benefits have come with unforeseen and unintended, yet no less crippling strings attached. The government has killed the private MBS market, and the Fed cannot withdraw its support, lest the tissue paper holding this precipitous together tear. By guaranteeing the agency8 mortgage-backed securities, whether implicitly through assumed QE from the Fed or explicitly through contractual guarantees with Fannie, Freddie and Ginnie, the non-agency part of the market cannot compete and is practically gone.

Before the GFC, the non-agency and agency security markets grew in tandem. But, since the Fed began buying agency mortgage-backed securities, non-agency MBS creation has dropped off in both absolute and relative terms. The non-agency securities are now less than 12% of the market. Why? No one can outbid the Fed. The federal guarantee underwriting these securities means that the government is on the hook if mortgage costs rise and households begin defaulting. So, as a non-agency MBS issuer doesn’t have this federal guarantee, investors will demand a default risk spread and, because of this, a higher yield. In turn, the non-agency progenitors of these securities must buy the underlying mortgages for less from the mortgage originators—banks, shadow banks, and credit houses. Q: Why would the bank accept a lower price for the same mortgage? A: They wouldn’t. Instead, if they have access to a government-sponsored enterprise, originators will sell to them at a higher price and recoup more money. The GSE will invariably acquire the mortgage to package and sell them to their primary customer, the Fed. The Fed will unfailingly buy the security from them because, well, they have to.

Mortgage lending, and the risks associated with it, have successfully been transferred from banks, mortgage houses, and investors to the public. Income and capital gains remain privatised, while hazards have become socialised. Not only does the U.S. government—and through them, the taxpayer—guarantee the agency securities, they also own 22% of them through the Fed. In addition, the public purse is earning paltry real yields of ever-so-slightly more than zero. These interest rates and returns are so subterranean that the private market thinks taking the risk is simply not worth it and is disappearing.

If the Fed tries to reduce its MBS holding, it will tank the market and mortgage costs will explode. A simple regression model suggests that should the Fed reduce its MBS holdings as a percentage of the overall market to its post-GFC average, 30-year real mortgage costs will triple from 0.5% to 1.5%. More concerningly, if they removed themselves entirely from the market, the 30-year real mortgage cost would sextuple to 3%. On the other hand, if the Fed doesn’t reduce its MBS position and continues buying, the ongoing effects of inflation will continue to drive real yields and real mortgage costs down. Purchasing power will continue being taken from savers and the taxpayer and given to mortgagers, while risk will continue being transferred to the public.

The Federal Reserve, much like Atlas the Titan in Hesiod’s Theogony, is trapped, condemned to spend eternity straining to hold up the sky, or more aptly, the roof.