Vol. 3, No. 6 — The bank the Bay built

The demise of Silicon Valley Bank. Stocks are fairly priced. The Fed rolls out a new bank liquidity support facility. Value in pork belly.

Welcome to Valuabl, a twice-monthly digital newsletter providing value-oriented financial market analysis and investment ideas. Learn more

In today’s issue

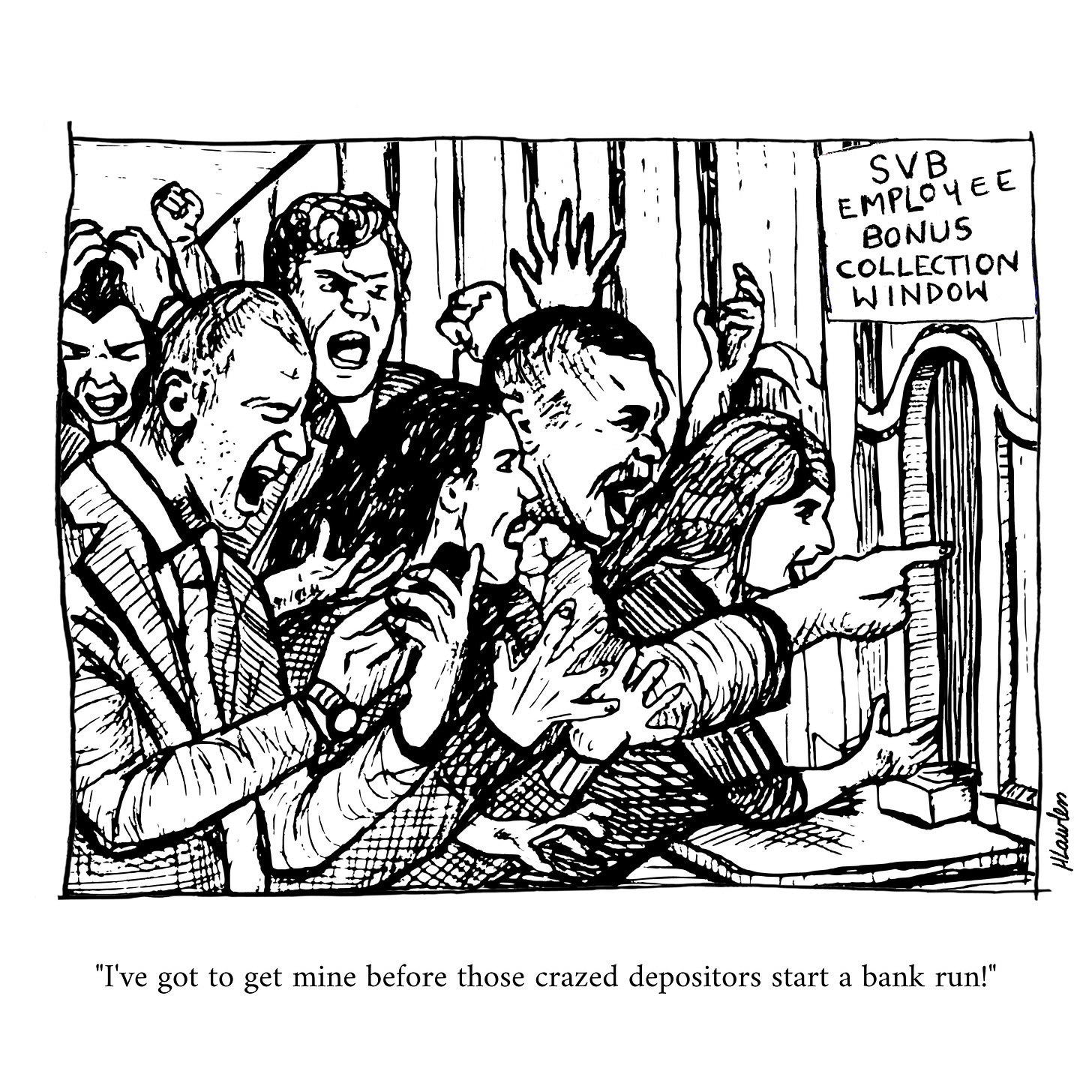

Cartoon: SVB bonus bank run

The bank the Bay built (6 minutes)

Cost of capital (3 minutes)

Global stocktake (3 minutes)

Rank and file (1 minute)

Credit creation, cause and effects (6 minutes)

Debt cycle monitor (1 minute)

Investment idea (13 minutes)

“The whole history of civilization is strewn with creeds and institutions which were invaluable at first, and deadly afterwards.” ― Walter Bagehot

Cartoon: SVB bonus bank run

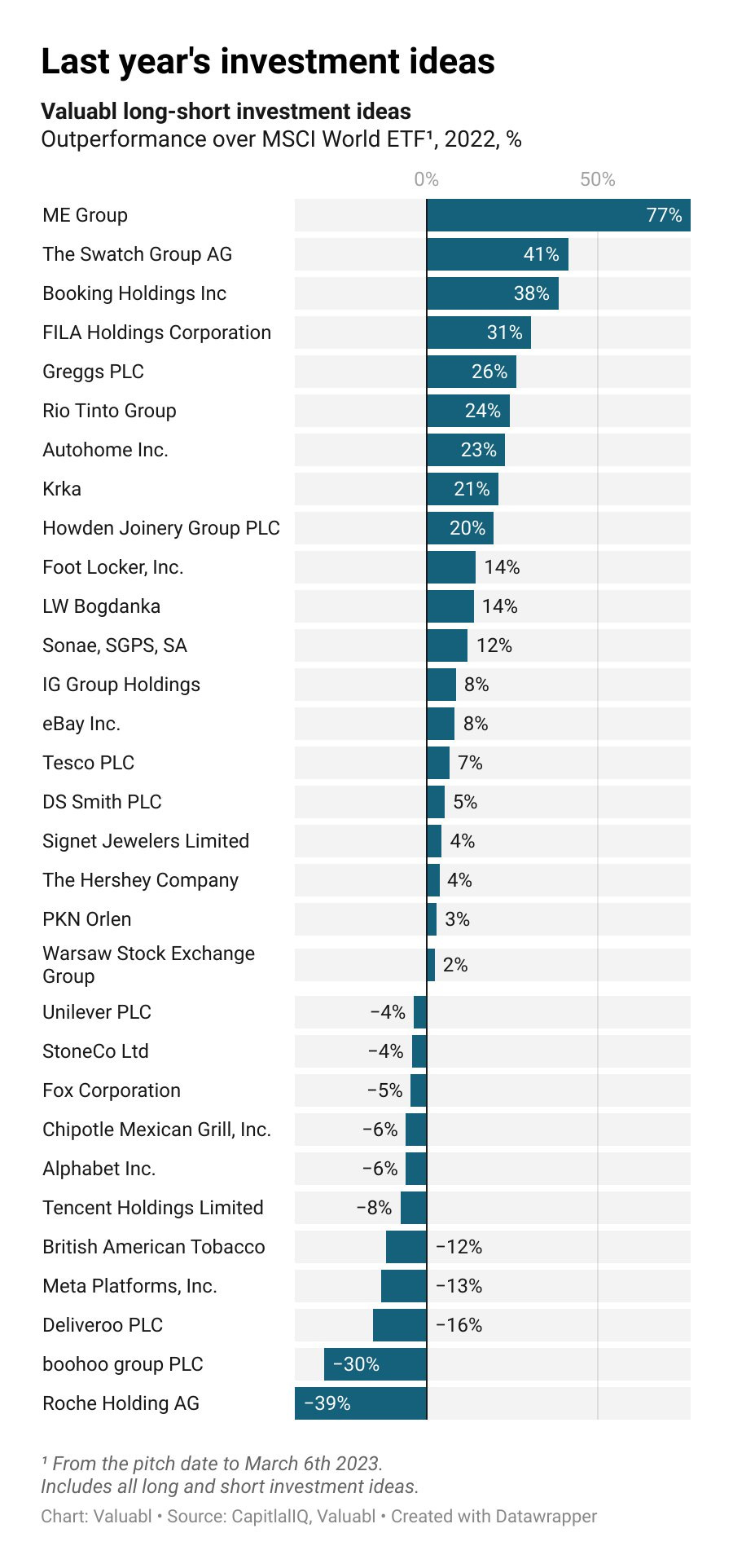

Update: 2022’s investment ideas

Last year, I pitched 31 investment ideas in Valuabl. 80% of Buy-rated ideas beat the market, producing a +24% annualised alpha.

Money talks—it just needs an interpreter

What would access to my best investment ideas do for your portfolio? Each issue of Valuabl has a rigorous analysis of the most undervalued stock I found that fortnight. Boost your risk-adjusted returns with my distinctive value-oriented analysis of global capital markets.

The bank the Bay built

It was the second-largest bank collapse in American history—and it went down at fibre optic speed

•••

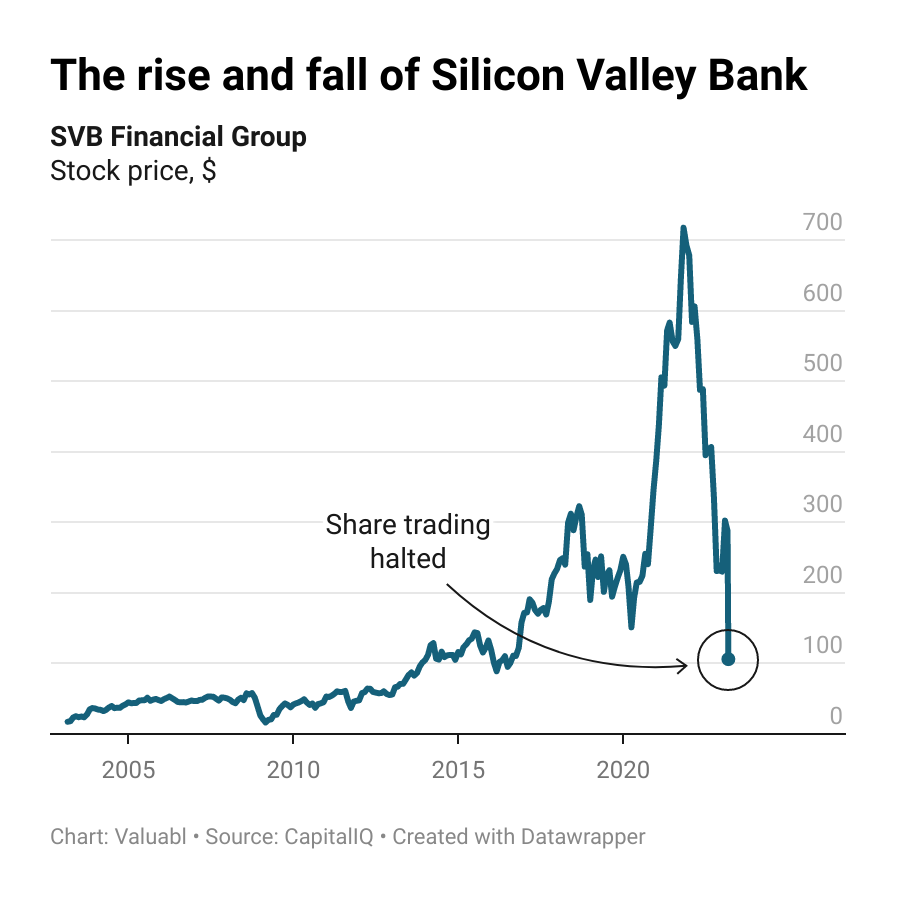

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), the bank for Bay Area tech startups, took a punt on interest rates staying low. They bought long-term bonds and hoped to profit. But interest rate hikes crippled the bank's capital base and left them almost insolvent. The firm's customers, most of whom had more than the $250,000 guarantee limit on deposit, panicked. They fled and tried to pull their money before others did.

It was an old-fashioned bank run, accelerated by the speed of digital banking. At the peak of the run, customers were pulling $500,000 per second, and the bank didn't have the money. This forced the regulator to step in and shut the bank. Within hours, the suits from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) had taken over.

The collapse wiped out shareholders, and bondholders will take buzzcuts. But that is not a failure of the financial system. Instead, the bank's bosses botched it, and a mismanaged business has gone bust.

Herein lies the problem. The bank had enough assets to cover deposits, but that process would have taken a long time. Many tech firms couldn't pay staff or suppliers, and sackings would have followed. Lawmakers feared the panic would spread and depositors would run on other banks. As a result, on March 12th, the government announced it would guarantee all SVB's deposits. Further, they said if asset sales don't cover costs, the gap will come from the FDIC fund, into which banks have paid.

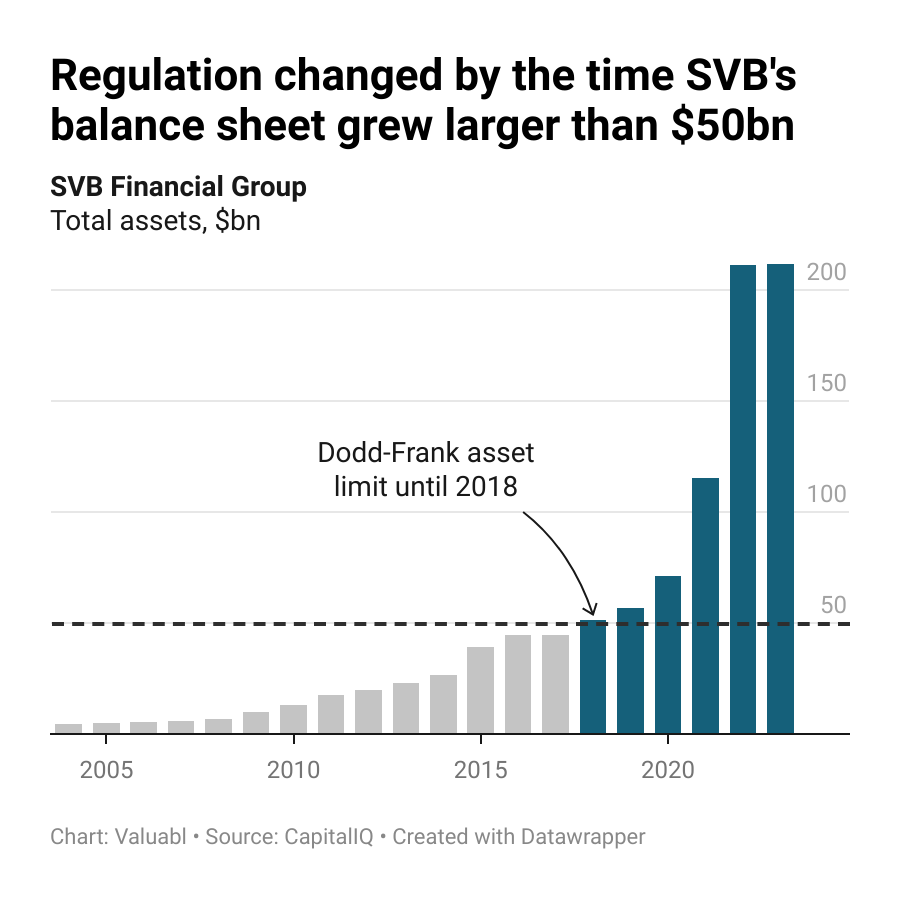

SVB's collapse was chaotic because the bank had been exempt from some parts of the Dodd-Frank Act, a series of regulations designed to prevent these kinds of improvised bailouts. As part of the rules, banks with more than $50bn in assets would have to hold more capital and pass stress tests. They would also have to have an orderly handover plan ready for if the bank failed. Finally, should a crisis hit and the bank need capital, bonds would automatically convert to equity. The idea was that fat layers of capital would prevent these big banks from dragging everyone else down if they collapsed. Share-and-bondholders, not depositors or the taxpayer, would pay the price.

But in 2018, the government diluted the regulations and raised the $50bn limit to $250bn. A group of banks, including SVB, lobbied for this and won. As a result, the bank could hold less capital, avoid stress tests, and couldn't get the emergency capital it needed. Instead of bonds converting to equity, the bank tried and failed to sell shares into a sinking market. Regulators were flying by the seat of their pants.

Emergency loans from the Federal Reserve should have been available to SVB earlier. The bank had plenty of good collateral, including Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). But the Fed was a day late and a dollar short. The central bank's job is to maintain financial stability, but they were too slow. If they had lent to SVB sooner, they could have averted the crisis and prevented the collapse of a major bank.

Walter Bagehot, the godfather of central banking, is spinning in his grave. Bagehot's dictum says that to avert panic, the central bank should not hesitate. It should lend early and without limit to solvent firms with good collateral. But it should also lend with punitive terms. That is almost what the Fed will now do to shore up other banks—but what it didn't do for SVB.

A new program will let banks borrow against government bonds and MBSs. Exactly like the ones SVB had mountains of. But, a facility like this would usually impose a price cut on the bonds used as collateral. This one won't. Instead, it will recognise the face value of the bonds—hair extensions as opposed to hair cuts. This generous support for banks is undue. It is a handout for bank shareholders. Although it will stop a crisis, subsidising banks for lousy interest rate bets is crummy.

Tighten the leash

The lesson lawmakers must learn is that banks are different from other businesses. They are public-private partnerships. The government gives them the right to create money, a public monopoly, but keep the profits. As such, bank regulation should serve the public purpose. Policymakers must realise this and fix it soon.

Cost of capital

Finance’s most important yet misunderstood price is capital. Here’s what happened to the cost of money in the past fortnight.

•••

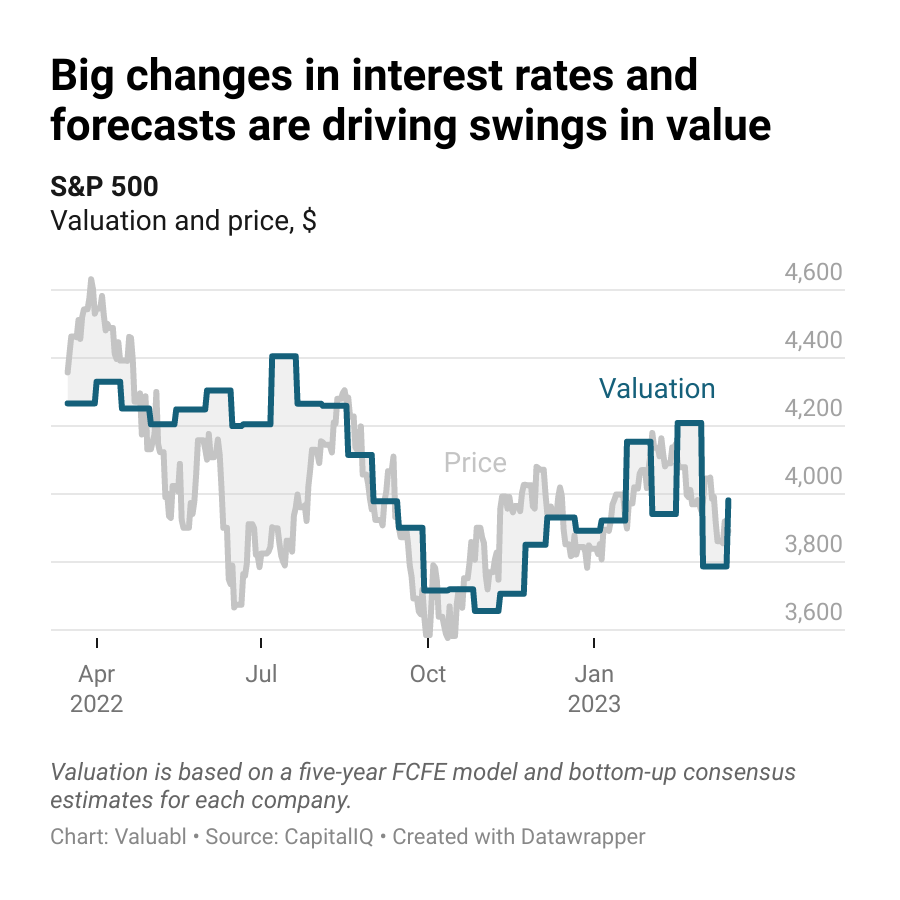

Stock prices fell last fortnight. The S&P 500, an index of big American companies, dropped 1% to 3,892. The market continues to rise from its October lows but is still 9% below where it was last year. Fears of a crisis after the collapse of SVB and Signature Bank have spooked investors.

I value the S&P 500 at 3,982, which suggests it is fair value. My valuation has thrashed back and forth in recent months. Significant movements in bond yields and consensus estimates are to blame. Traders and analysts are uncertain about the future, which has shown up in estimates.

The companies in the index earned $1,627bn in the past year. They paid out $516bn in dividends, bought back $981bn worth of shares, and issued $72bn of equity.

The forward price-earnings (PE) ratio shrunk to 16.9x. My 12-month forward earnings per share (EPS) estimate for the index climbed from 229 to 230.

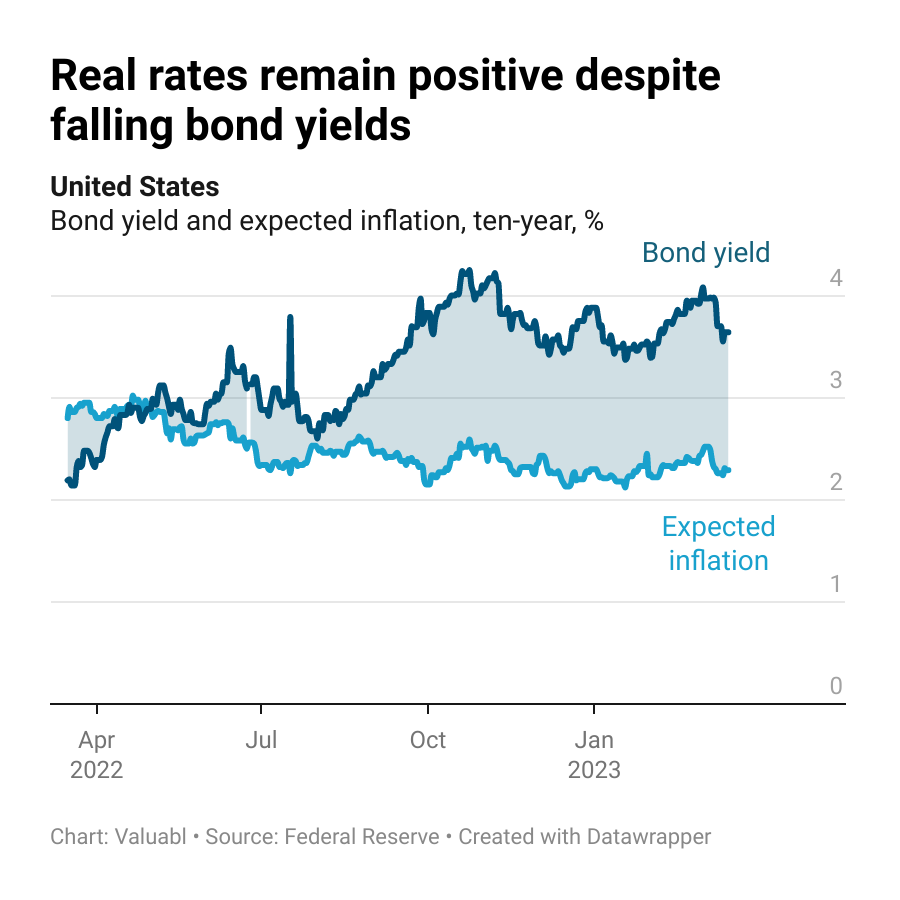

Government bond prices rose as investors sought safety. Yields, which move the opposite way to prices, fell. The ten-year Treasury yield, a critical financial variable, dropped 37 basis points (bp) to 3.6%. Investors expect inflation to average 2.3% over the next decade, down 55bp in the past year.

The real interest rate, the gap between yields and expected inflation, shrunk by 22bp to 1.3%. Still, these inflation-adjusted rates are up over two percentage points in the past year.

Corporate bond prices also went up. Credit spreads, the extra return creditors demand to lend to a company instead of the government, shot up 24bp to 1.8%. While the cost of debt, the annual return lenders expect when lending to these companies, fell 13bp to 5.5%.

Refinancing costs are up 1.5 percentage points in the past year. The ruckus caused by SVB and Signature banks’ collapse has pushed up the price of risk.

The equity risk premium (ERP), the extra return investors want to buy stocks instead of bonds, lept 33bp to 5.3%. It’s now about the same as it was a year ago. The cost of equity, the total annual return these investors expect, fell 4bp to 8.9%. These expected returns are a little above their long-term average.