Vol. 3, No. 10 — The glass ceiling

Lawmakers should remove America's debt ceiling; The S&P 500 is fairly valued; Energy stocks are cheap; The case of the missing deposits; Value in pharmaceuticals

Welcome to Valuabl, a twice-monthly newsletter providing financial analysis with a value-oriented perspective. Valuabl is here to help bankers and fund managers make smarter investment decisions. Learn more

In this issue

Cartoon: Credit where credit’s due

The glass ceiling (9 minutes)

Cost of capital (3 minutes)

Global stocktake (3 minutes)

Rank and file (1 minute)

Credit creation, cause and effects (6 minutes)

Debt cycle monitor (1 minute)

Investment idea (12 minutes)

Quotation

“The United States can pay any debt it has because we can always print money to do that. So there is zero probability of default.”

— Alan Greenspan, former Federal Reserve Chairman

Cartoon: Credit where credit’s due

The glass ceiling

American lawmakers are too busy debating whether to raise the debt ceiling to realise they should end it altogether.

•••

On the side of a Manhattan building near Times Square, the National Debt Clock ticks ever higher. Seymour Durst, a developer, set up the display in 1989 to draw attention to what he saw as the nation's debt problem. But the number's smooth climb has made it easy to forget. The clock now ticks above $31trn, a leap from the $3trn number it displayed when Durst first installed it.

The debt's relentless climb poses a risk to the global economy, not because of its size, but because it will soon reach its legal limit. The debt ceiling, the made-up amount Congress allows the government to borrow, stands at $31.4trn. America is almost there. Last week, Janet Yellen, the head of the Treasury, warned that the state will run out of cash by June. She said the government won't be able to pay its bills and will default, unless politicians raise the country's credit limit.

Should lawmakers do this? Ms Yellen and the Democrats think so. But Republicans are against it. They argue the government should live within its means. They believe that default is the price creditors and the government should pay.

While failing to raise the ceiling would be disastrous, increasing it is only a temporary fix. Instead, lawmakers should consider getting rid of the cap altogether. While this is unlikely, it is the best thing to do. The debt ceiling creates unnecessary risks, and there is no good reason for it to exist.

First, we see the same political posturing whenever the debt pushes up on the ceiling. The party in power says Congress must raise the limit, while the opposition says no. The minority party calls those in charge reckless and spendthrift. They demand spending cuts and tax hikes in the name of fiscal responsibility. The fear of default makes the economy and markets less stable. Eliminating the ceiling altogether would remove the uncertainty and risks it creates.

Since 1990, legislators have raised the country's credit limit 31 times. On average, in the four-week lead-up to each decision, the VIX, a measure of market volatility, climbed 6%. Investor uncertainty over whether the state will pay its bills weighs on sentiment. Markets and investment drop. People panic at the prospect of hospital closures and starving pensioners.

Further, markets churn at the threat of default on the world's safest asset, Treasury bills. Yields on those bonds climb 10bp on average in the month before the ceiling decision. In fact, the prospect of default caused S&P, a credit rater, to downgrade the US government from AAA to AA+ in 2011. It was the first time analysts called America's creditworthiness into question.

If the debt ceiling isn't raised, the government will have to default on its obligations. An economic crisis would ensue as the asset underpinning global finance collapses. But by pushing the debt ceiling up, it kicks the can down the road. The debate and fear-mongering happen again and again.

The US government's solvency should never be in question. But the problem is not about whether to raise the ceiling; it's the ceiling's existence. Without it, politicians couldn't spread fear to pursue a political agenda.

Next, there is no functional reason for the debt ceiling to exist. Constraining the government's solvency is a needless handbrake on the modern monetary system. It's a byproduct of a bygone era.

The debt ceiling is a hangover from the gold standard. Back in 1917, when legislators introduced it, the government had to get gold to spend it. Whenever the Treasury wanted to issue bonds, borrow and spend, Congress had to approve it. But that was a slow process. With the time and cost pressures of the First World War, they voted to create a borrowing limit instead. The Treasury could borrow the money needed to buy the gold that enabled its spending. But the modern monetary system doesn't run on gold anymore. Fiat money governments, creators of money without backing, spend before they collect.

The government creates money when paying for something, not when borrowing. When a public worker gets their paycheque, the Treasury's account at the Fed goes down, while the employee's goes up. The government is a monetary scorekeeper. It doesn't need money to spend it. There's no mechanical reason the Treasury account can't go negative and act as a free overdraft at the Fed. When the central bank buys Treasury bonds from banks, the net effect is the same as a free overdraft.

Fiscally responsible irresponsibility

Yet, the main argument for the debt ceiling is it constrains government spending. The government must be fiscally responsible and pay down its debts. It must live within its means. Without a debt ceiling, politicians would mortgage the country's future. So the reasoning goes.

But this point doesn't tread water. The government has raised the debt ceiling whenever it wanted. Since 1940, lawmakers have upped the limit 82 times—once a year on average. In fact, the last time they lowered it was June 25th 1963, some 60 years ago. The same people who decide how much to spend are the ones who choose the credit limit. If regulators put the ceiling there to enforce fiscal discipline, it has failed. Federal government debt as a percentage of GDP is 110%, almost the highest level ever.

The other reason ceiling advocates give is that debt is burdensome. But this logic also falls down. Since the government creates the money, it can always pay. It doesn't need to raise taxes to pay off or maintain the debt. Government debt is also a financial asset for the private sector. It represents actual savings. Those bonds are out there as savers want them. But if interest payments seem too big, the Fed can buy as many bonds as needed. The government would then be paying interest to itself.

If political bickering continues, this will spread more fear, uncertainty and doubt. That will stress the millions of people who need government payments. Financial markets will reel. Cash savings will increase, and economic activity will decline. Government spending will drop to the tax receipt level, but that will also fall. The White House reckons a default would be catastrophic. They estimate that it would cause 8m job losses in one quarter. Real GDP would fall 6%, and the stock market would implode, shedding 45% of its value. While raising the ceiling is a temporary patch, they must do it. But, unless we want to face this problem year in and out, the only real solution is to erase the limit altogether.

"The limit does not exist!" — Cady Heron, Mean Girls

Cost of capital

Finance’s most important yet misunderstood price is capital. Here’s what happened to the cost of money in the past fortnight.

•••

Stock prices rose last fortnight. The S&P 500, an index of big American companies, climbed 2% to 4,138. The market is now 3% higher last year. Remarkable given that interest rates have climbed from 1% to 5% in that time.

I value the index at 4,016, which suggests it is fair value. My valuation, which thrashed about in the first quarter, has stabilised. Analysts have become more confident about future earnings, and bond yields are steady.

The companies in the index earned $1,642bn in the past year. They paid out $504bn in dividends, bought back $923bn worth of shares, and issued $68bn of equity.

The forward price-earnings (PE) ratio rose to 17.7. My 12-month forward earnings per share (EPS) estimate for the index also climbed from $231.40 per share to $233.40.

Government bond prices fell. The ten-year Treasury yield, which moves the opposite way to prices, jumped ten basis points (bp) to 3.5%. Investors expect inflation to average 2.2% over the next decade. Their inflation forecast has fallen 48bp in the past year.

The real interest rate, the gap between yields and expected inflation, rose 18bp to 1.4%. These inflation-adjusted rates have been positive for a whole year.

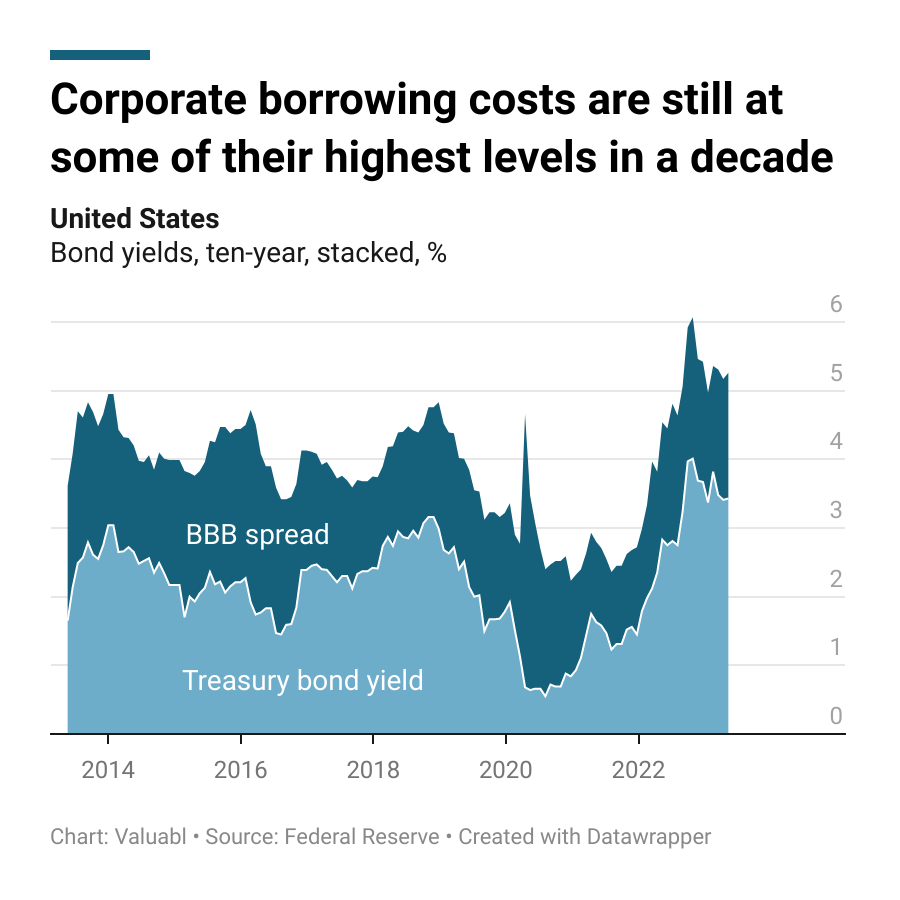

Corporate bond prices also fell. Credit spreads, the extra return creditors demand to lend to a company instead of the government, climbed 10bp to 1.8%. While the cost of debt, the annual return lenders expect when lending to these companies, rose 20bp to 5.4%.

The equity risk premium (ERP), the extra return investors want to buy stocks instead of bonds, fell 3bp to 5%. It’s now 16bp below where it was last year. The cost of equity, the total annual return these investors expect, rose 7bp to 8.6%. These expected returns are in line with their long-term average.