Vol. 3, No. 9 — Landing a new tax

Existing taxes should be replaced with a single land tariff; Stock valuations have stabilised; Traders think a recession is inbound, but deficits and lending make that unlikely; Value in Post-it notes

Welcome to Valuabl, a twice-monthly newsletter that provides analysis to help you make smarter investment decisions. New here? Learn more

In today’s issue

Cartoon: Twirling, twirling towards freedom

Landing a new tax (8 minutes)

Cost of capital (3 minutes)

Global stocktake (3 minutes)

Rank and file (1 minute)

Credit creation, cause and effects (7 minutes)

Debt cycle monitor (1 minute)

Investment idea (23 minutes)

Quotation

"When everyone believes something is risky, their unwillingness to buy usually reduces its price to the point where it's not risky at all. Broadly negative opinion can make it the least risky thing since all optimism has been driven out of its price."

— Howard Marks, The Most Important Thing

Cartoon: Twirling, twirling towards freedom

Landing a new tax

The current tax system is inefficient and unfair. Lawmakers can fix it by replacing all current taxes with a single land-value tax. This would cure the housing crisis, stimulate economic growth, and reduce inequality.

•••

The tax code's complexity and inefficiency are part of the problem—America's is over 4m words long. Political jawboning is also to blame. Lawmakers say a lack of supply has caused the housing crisis, yet they do nothing to fix it. But why would they? They, and their homeowning voters, are financial beneficiaries.

So, what should the government do to repair the broken tax system? One solution is to replace all national taxes with a land-value tax (LVT). That tax would be a single annual tariff paid as a proportion of the value of the land—but not the buildings—someone owns. But, the government would need to drop all other taxes to make it work. If they did this, the economy would boom. With taxes on shopping, work, and business all gone, everyone would save time and money. Currently, the average firm spends 240 hours each year working out and paying its taxes—what a waste. Further, productive land development would resolve the housing crisis. A fairer, more efficient economy awaits.

First, a land-value tax is fairer than the current system. Even the most crusted-on supporters of property rights have struggled to justify how land ownership could originate, given it deprives others of a natural resource. In his 1776 book, The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith wrote that the value of land comes from the natural resources and opportunities it provides. He argued that it didn't come from the effort or skill of the landowner. Because of this, he reckoned it is fairer to tax landowners on the value of their land rather than workers on their income or wealth.

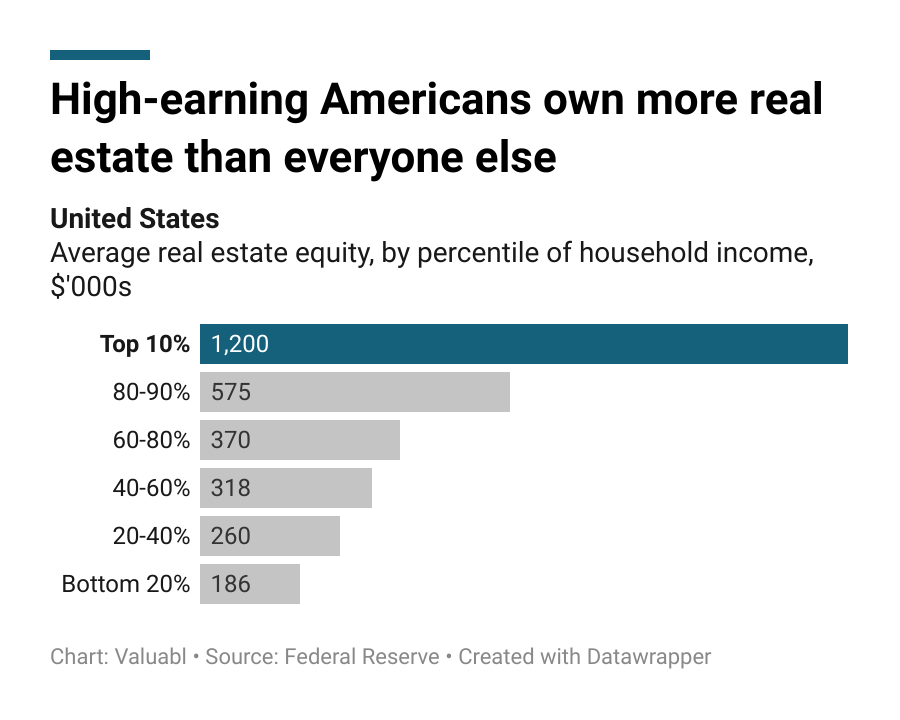

Further, large companies and high-income households own more land than poor people. They're most able to afford the tax. While they can pay accountants to help them avoid other types of taxation—a luxury poor people can't afford—it's impossible to offshore land. The tax would, as a result, be unavoidable. That solves a problem that has plagued lawmakers for the past few decades: how to crack down on tax evasion?

Second, a land tax would be easier to administer than the current system. Since it is unavoidable, there would be no need to lodge financial statements or tax returns. You cannot take land offshore or not declare it. The government knows what land there is. In the case of an unpaid tax bill, the government would repossess and auction the land. Fancy accounting gimmicks and legal chicanery wouldn't work. Public sector employees who track taxes could move to other public services. The IRS, America's tax man, has 79,000 people working there, costing $14bn each year. The state could cut much of that expense and move workers into jobs that better serve the public.

Switching to a land tax would also cut business compliance costs. PwC, an accounting firm, reckons companies worldwide spend 48bn person-hours and $178bn per year on tax compliance. That works out to 240 hours per year per firm—a lot of wasted time and money. By liberating these resources, companies can reinvest more in development and growth.

Third, this tax would incentivise development, with the productive use of land leading to an economic boom. With a fixed tariff, the better utilised the ground, the smaller the tax becomes as a percentage of revenue. Landowners in busy cities would build apartments to make more rent and lower their tax burden. And if they don't want to or can't, the tax would force them to sell to someone who can. This would cure the housing crisis at its source. Land speculation and hoarding would become unprofitable, but good developers would make money.

For example, The Pittsburgh Experiment, a Lincoln Institute of Land Policy group study, showed that the city's 1979 LVT led to an economic boom. They found that taxing land separate from buildings decreased the prevalence of vacant and abandoned land by 31%. They also found it spurred development and increased the city's tax base.

However, naysayers argue that a land tax would increase rent or be unaffordable for homeowning families. The argument is that the landlord will pass on the tax by raising leases. Then businesses, in turn, will up their prices. As a result, consumers would end up paying the landlord's tax anyway.

But, by cutting sales and company taxes, businesses could lower prices and keep the same profits. With a lower compliance burden, entrepreneurs could more easily create new companies. Competition would push prices down and slash the extra profits businesses would get from the tax cuts. Moreover, as landowners develop their space, the supply of usable real estate will increase. With more real estate, landlords would compete more vigorously, stifling rent raises.

Next, a land tax would not be unaffordable for homeowners. According to data from the latest Federal Reserve's Flow of Funds report, the total value of all private land in America is $37trn. For the LVT to cover the US federal government's current receipts of $3.2trn per year, they would need the equivalent of a 9% annual tax on the current value of land. This is $11,300 per year for the median American homeowning household, or 16% of their income. That estimate is not perfect, and implementation would work differently, but it illustrates it’s hardly a prohibitive cost. Especially given that eliminating all other taxes would dramatically boost workers' purchasing power.

The productivity incentives created by the tax would lead to more affordable housing and a more dynamic economy. Households and workers would benefit. In contrast, keeping with the current tax system will perpetuate the housing crisis and deepen inequality.

Putting the real in real estate

The current tax policy is not working. Tax breaks incentivise unproductive land hoarding while disincentivising work and investment. The enormous compliance burden gives big businesses and the rich an unfair advantage. The government can make the economy more dynamic by switching to a land-value tax. That would fix the housing crisis, stimulate growth, and reduce inequality. Doing nothing but talking, as our lawmakers have so far, will only add to the misery.

Cost of capital

Finance’s most important yet misunderstood price is capital. Here’s what happened to the cost of money in the past fortnight.

•••

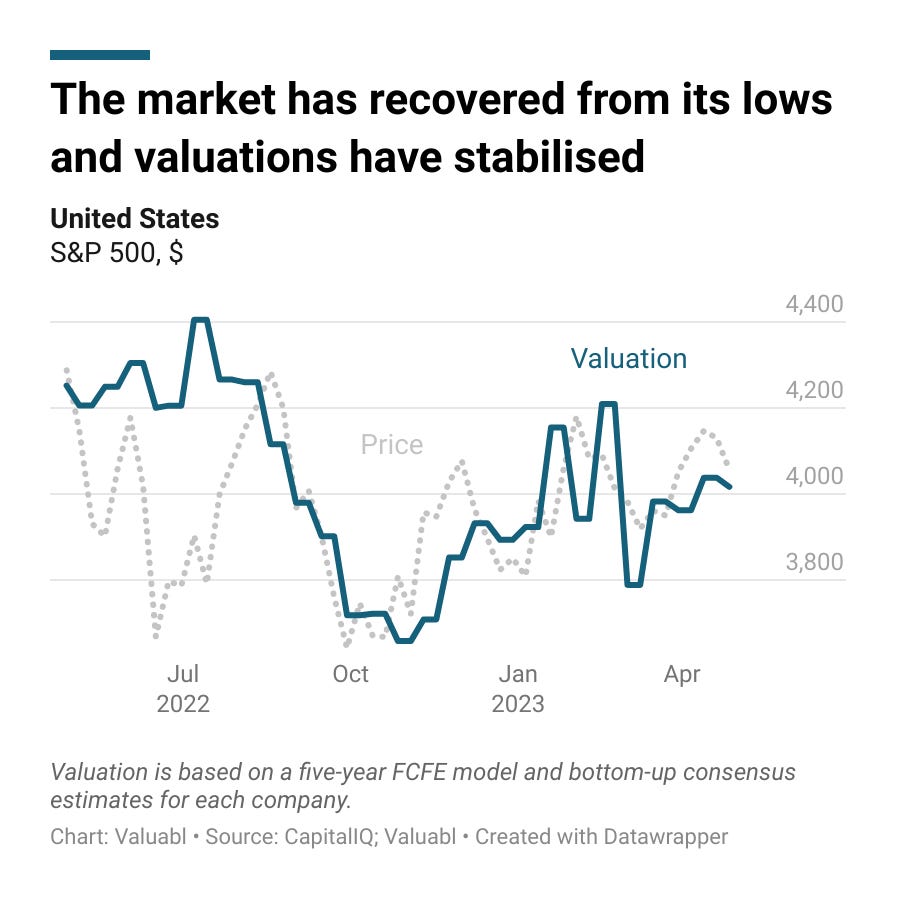

Stock prices fell last fortnight. The S&P 500, an index of big American companies, dropped 1% to 4,056. The market is up from its October lows but still 3% below where it was last year.

I value the index at 4,016, which suggests it is fair value. While my valuation thrashed back through the first quarter, it’s started to stabilise. Big gyrations in bond yields and consensus estimates were to blame. But markets and estimates have calmed down.

The companies in the index earned $1,622bn in the past year. They paid out $462bn in dividends, bought back $898bn worth of shares, and issued $68bn of equity.

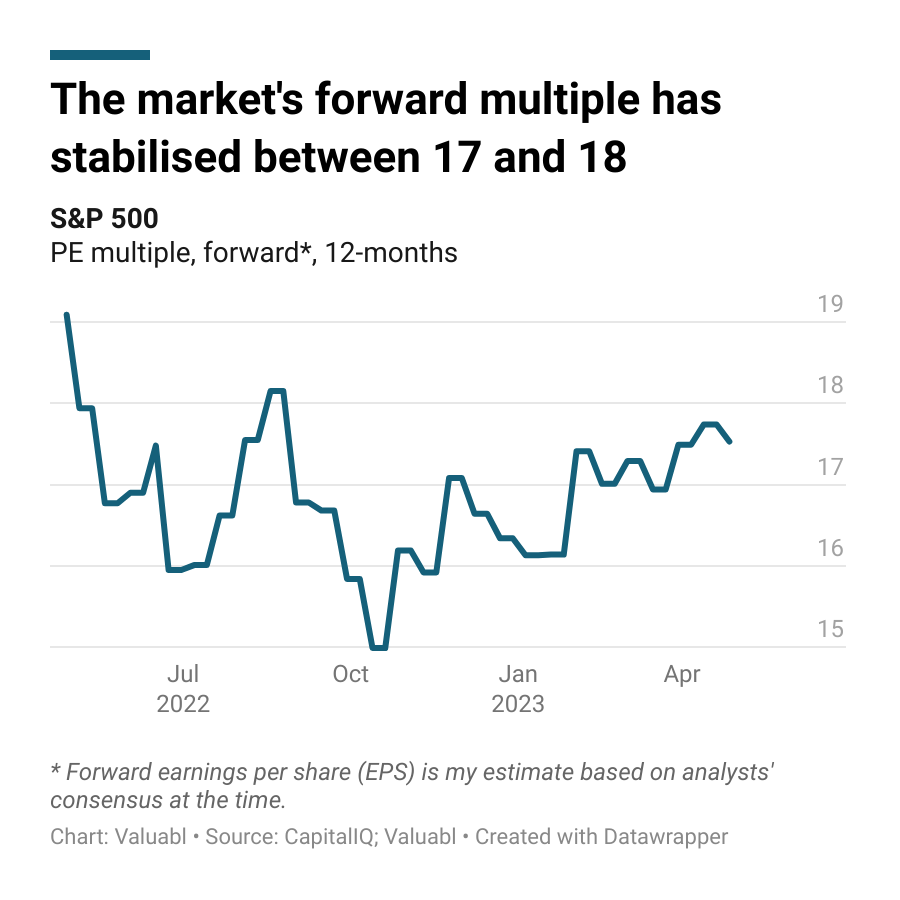

The forward price-earnings (PE) ratio dropped to 17.5. My 12-month forward earnings per share (EPS) estimate for the index also climbed from $230.60 per share to $231.40.

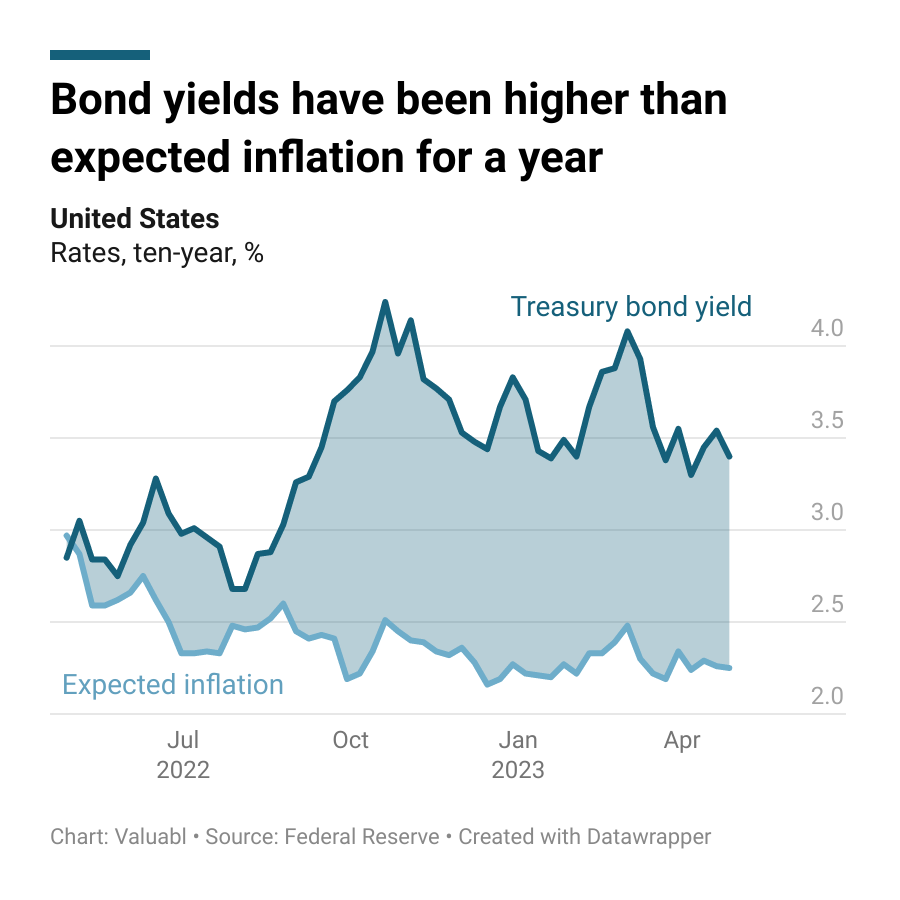

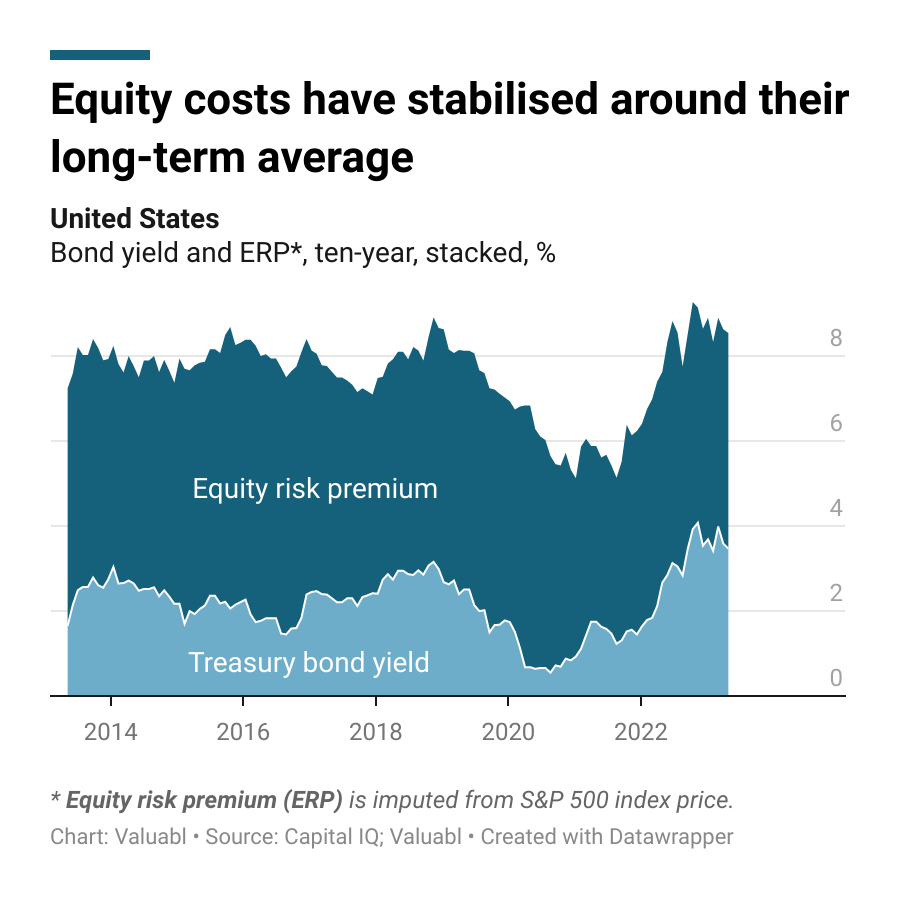

Government bond prices rose a tiny bit. Yields, which move the opposite way to prices, dropped. The ten-year Treasury yield, a critical financial variable, fell one basis point (bp) to 3.4%. Investors expect inflation to average 2.3% over the next decade. Their inflation forecast has fallen 60bp in the past year.

The real interest rate, the gap between yields and expected inflation, rose one bp to 1.2%. Still, these inflation-adjusted rates have been positive for a whole year. They’re 123bp higher than where they were 12 months ago.

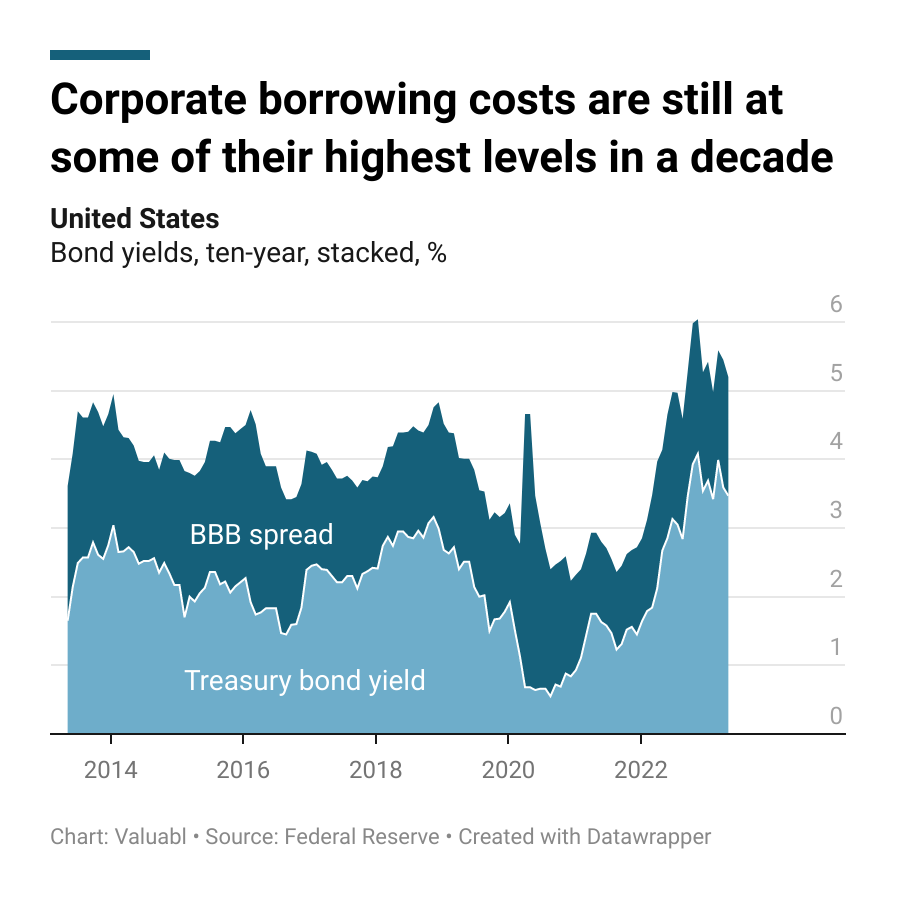

Corporate bond prices rose. Credit spreads, the extra return creditors demand to lend to a company instead of the government, dropped 4bp to 1.7%. While the cost of debt, the annual return lenders expect when lending to these companies, fell 4bp to 5.1%.

Refinancing costs have risen 71bp in the past year. The ruckus caused by SVB and Signature banks’ collapse, which had pushed up the price of risk, seems to be subsiding.

The equity risk premium (ERP), the extra return investors want to buy stocks instead of bonds, rose 2bp to 5.1%. It’s now 12bp above where it was last year. The cost of equity, the total annual return these investors expect, rose 1bp to 8.5%. These expected returns are in line with their long-term average.