Vol. 4, No. 10 — Hear no evil, speak no evil, own no evil?

The moral and investment case for owning evil stocks; Big tech will continue to eat the world; Bank stocks are finally cheap; An undervalued digital content business

Contents

The world this fortnight

Leader | Hear no evil, speak no evil, own no evil?

Letters to the editor

Finance | Software is still eating the world

Finance | Bank on it

Cost of capital

Investment idea | Value in digital content

Economic and financial indicators

The world this fortnight

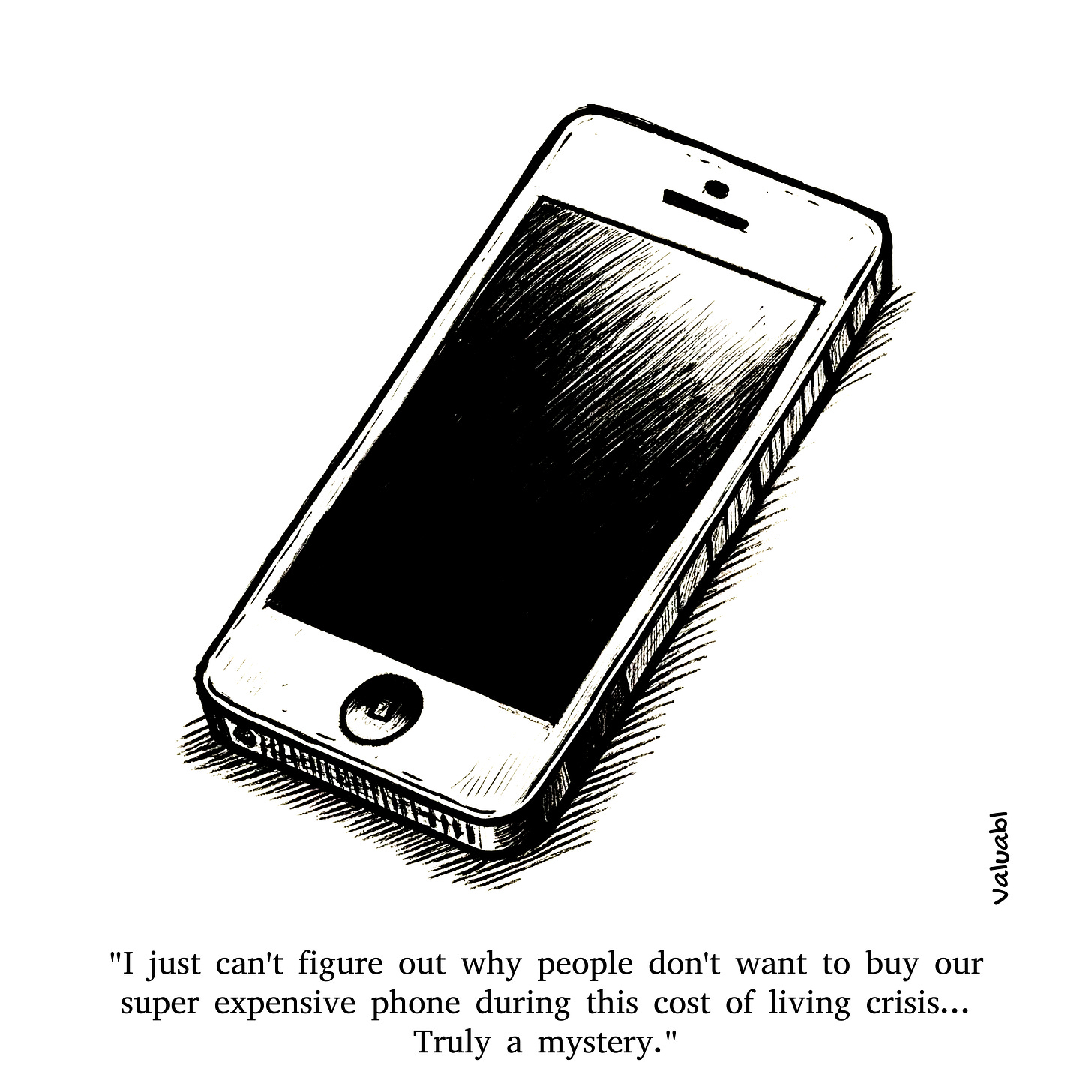

Apple, the iPhone maker, announced its second-quarter sales and earnings figures, beating analysts' estimates. But it was a close call. The company's earnings per share figures were just 1% above analysts' forecast, while sales fell 4% year-on-year. It blamed a significant drop in iPhone sales in China for the stunted result. The rumour-mil has also been working overtime as punters speculate that Tim Cook, the company's boss, will soon retire. After taking over from an ailing Steve Jobs, he's held the top job for 13 years.

The world's largest online retailer, Amazon, also announced earnings. The company's top line grew 12.5% last year, while earnings per share were 19% higher than analysts had predicted. Amazon's boss, Andy Jassy, said the artificial intelligence boom was helping Amazon's Web Servers (AWS) business. AWS now pulls in $100bn of revenue a year.

In the first quarter, Saudi Arabian oil giant Aramco beat estimates, too. The company pumped 12.8m barrels of the black stuff out of the ground and made a $31.9bn net profit. Still, analysts do see much upside from the current level. The 15 analysts who cover the stock have assigned a $33 average price target, just 10% above its current price.

The Federal Reserve left interest rates on hold. The target federal funds rate, which is the rate banks lend reserves to each other, is still 5.25-5.5%. It's been at that level since July last year. Bank chairman Jerome Powell acknowledged that while inflation has come down over the past year, it's still too high for them to cut rates. He clarified that he doubts they'll raise rates any time soon but that the bank will reduce the pace of its quantitative tightening program next month. The bank will remove up to $25bn of Treasury securities per month from their stash, down from the previous $60bn limit.

The proportion of Americans looking for but unable to find work rose slightly. Just 3.9% of Yanks were unemployed in April compared to 3.8% the month before. The unemployment rate has been steadily climbing. It was at just 3.4% in April last year. At the same time, the number of job openings per person looking for a job has been falling.

Across the pond, the Bank of England also left rates on hold at 5.25%. Andrew Bailey, the bank's governor, said a rate cut in June is neither "ruled out nor planned." Still, two of the monetary policy committee's nine members voted to cut rates. The bank forecasts that rate cuts are coming later this year.

The British economy shrank by 0.3% in last year's final quarter, far below economists' 0.4% growth forecast. That marks two quarters in a row of economic contraction and means the country is in a technical recession. High borrowing costs and weak external demand have hammered spending.

Leader | It’s good to own evil stocks

Hear no evil, speak no evil, own no evil?

Why people who see themselves as moral value investors should own evil companies

"There's some good in this world, Mr Frodo, and it's worth fighting for." So said Samwise Gamgee in the movie version of "The Lord of The Rings: The Two Towers." The scriptwriters, who dreamed up the line, thought it might come across as cheesy but decided to leave it in any way. And thank goodness they did—it's become iconic. But what does good mean? To Frodo and Sam, it meant destroying the ring and getting back their idyllic lives in The Shire. To others, it means avoiding being protested by woke university students. And to many value investors, it means not taking a position in any companies they see as immoral.

The sanctimonious among us won't invest in coal mines or cigarette makers because they think soot and smokes are nasty. They reckon that the companies who make those things are evil. They don't want their dollars going to support those causes. However, their logic is misguided. It's precisely because these investors think those companies are evil that they should invest in them. By doing that they will enjoy better returns, help prevent money from getting into the hands of folks they deem evil, and they can affect change.

First, you should invest in companies you think are evil because it will help prevent the wrong sorts of people from benefitting from that business's cash flows. All companies have an owner. Someone receives the company's dividends whether you like it or not. If you view yourself as good and think you'll do moral things with your money, you should buy evil companies from bad people. That will stop those villains from profiting from those businesses. After all, if you see them as evil, surely you want to prevent them from enjoying those profits?

Imagine it's the 1940s, and a large investment bank is selling, for cheap, a big malevolent company that makes lots of money. All else being equal, would the world be better off if the Nazis or The Red Cross bought it? If the Nazis owned it, they would get regular profits and dividends to help fund death camps and the war machine. If The Red Cross owned it, they would have more money to save lives. If you see yourself as a moral investor and don't buy evil companies, you demonstrate that you're okay with evil people enjoying those profits.

That is the same collective agreement most rich countries' citizens have already made. By taxing booze and tobacco makers, for example, more than other companies, governments show that they want a bigger slice of evil companies' pies. We've all indirectly said, give us a big piece of the ownership of those firms' profits, and we'll use that money for good. Lawmakers justify that extra tax because they use it to fund healthcare and education, both virtuous things. But actually, it's an entity, the state, that wants to own a piece of an evil company to use the profits for what it sees as good. Many people identifying as moral investors have already accepted this logic without realising it.

You should also buy evil companies because competition will force them to act better in society's eyes. By investing in those companies, you're contributing to lowering their cost of capital. A lower cost of capital means companies in that industry can raise money and reinvest more than they otherwise would. That drives up competition, which lowers the prices these evil companies charge. Consumers will have more selection and control over which firms they buy from. And, all else equal, they will go for the company they collectively see as the most ethical.

Whereas, if people collectively sell those evil stocks, their cost of capital will rise. Instead of raising money, companies in that space will divest. Competition will decline, and consumers will have less choice. Shoppers will be stuck with the most ruthless and amoral suppliers. By investing in evil companies, you'll contribute to the moral improvement of the industry. If you don't, you'll let it decline, and the most evil incumbents will become even more dominant.

If you see yourself as a moral investor, you should also invest in evil companies because they're cheap—people don't want to own them. According to data from Capital IQ, evil companies tend to trade at lower forward price-to-earnings (PE) and price-to-book (PB) ratios than non-evil ones. The average forward PE ratio for an evil company was 16x, while 23x for non-evil ones. This sample looked at the 20,000 largest companies by market capitalisation.

Of course, whether or not these industries are evil is subjective. However, governments love to vilify and crack down on these sectors, suggesting most see them as the bad guys. Still, other factors could explain why they trade at lower multiples. Perhaps they're systematically riskier? In fact, they're not. Both evil and non-evil companies in the sample have an average beta of one. Maybe they'll grow more slowly? Again, the difference is negligible. Analysts forecast an average two-year revenue growth rate for evil companies of 8.6% and 9.0% for good ones. As a result, the expected returns on evil stocks are better on average than for good ones. It turns out you must be bad to be good. ■

Letters to the editor

Argentinian inflation

You argued that Argentina should stop raising public sector wages to help slow inflation (“Hatchet job” Vol. 4, No. 8), but you did not explain why this would help. Further, you suggested that the government should give a job to everyone who wants one to try and reduce poverty. That would clearly make inflation worse. I suggest you think your ideas through a little more.

— David Miller, Sydney

Shorting cocoa

Thank you for the coca short trade idea (“Is it time to short cocoa?” Vol. 4, No. 9). It was spot-on. The analysis was clear and useful, which I believe many of your readers, including myself, found beneficial. Keep them coming. Hopefully, your timing is always just as good.

— Ben Evans, London

Reply directly to this email or send your commentary, critiques, and rebuttals to valuabl@substack.com. You can also direct message ValuablOfficial on X. Please include your name and city. Letters may be edited for brevity.

Finance | Big tech will grow fast

Software is still eating the world

Tech giants have taken over our lives, and the biggest ones will keep getting bigger

In 2011, Marc Andreessen, an American tech investor, wrote in the Wall Street Journal that “software is eating the world.” He was right, and his words still ring true today. Software is taking over everything. It’s taken over entertainment, work, and communication. It’s even dominating how we get around, order food, and shop.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has accelerated this trend. It’s already making companies much more productive and profitable. Law firms, for example, are hiring fewer graduates to trawl through legal documents. After all, AI can do it in a fraction of the time for a fraction of the cost. AI is also more accurate than a team of caffeinated but exhausted youngsters. That is precisely why software is taking over. It helps businesses run more smoothly and at a lower cost. Companies that embrace software can provide new services that are both cheaper and more convenient than traditional methods.