Vol. 4, No. 13 — Artificial or intelligent?

The NVIDIA bubble; Chinese stocks offer value and growth; Inflation will remain stubbornly high; A technology stock with a 50% upside

Contents

The world this fortnight | A summary of economic and financial news

Leader | Artificial or intelligent?

Letters to the editor | On Mexican takeaway, AI and stock dilution

Finance | Made in China

Economics | Inflation will remain stubbornly high

Cost of capital | Analysis of the ever-changing price of money

Investment idea | A technology stock with a 50% upside

Economic and financial indicators | Economic data, markets and commodities

The world this fortnight

Adobe, a software maker, reported a robust second quarter. The firm brought in $5.3bn of revenue, up 11% from last year. Earnings per share (EPS) rose 15% to $4.48. Shantanu Narayen, the company’s boss, said artificial intelligence (AI) boosted productivity. He bumped up the firm’s revenue and profit targets for the year.

Computer chip and software company, Broadcom, also announced a solid second quarter. The firm’s top line grew 43% year-on-year to $12.5bn, driven by VMWare, its virtual operating system software. The company’s boss, Hock Tan, said he reckons revenue will reach $51bn this year, and AI will contribute $11bn of that. The firm also announced a ten-for-one stock split.

Oil and natural gas behemoth, Shell, plans to buy European and Singaporean natural gas assets from Temasek Holdings, an investment conglomerate. The deal, which analysts reckon will close soon, is valued at hundreds of millions of US dollars and will make Shell the largest natural gas supplier to Singapore.

It was also a decent quarter for software maker Oracle. The company announced that revenues climbed 4% from last year to hit $14.3bn for the quarter. As is the theme, cloud services and AI were the key drivers. Safra Catz, the chief executive officer, said that the firm signed its largest-ever sales contract and plans to partner with ChatGPT marker OpenAI, as well as Google and Microsoft. The firm expects double-digit revenue growth this year and next.

America’s central bank, the Federal Reserve, decided to keep interest rates steady. The bank currently targets a rate between 5.25% and 5.50% and said it doesn’t expect to cut rates until inflation nears its 2% target—it’s currently at 3.3%, with rising energy costs hampering efforts to bring it down. Economists only see one rate cut coming this year, down from the three they projected in March.

Across the pond, the Bank of England also kept its interest rate steady at 5.25%, although some policymakers advocated for a cut. Recent indicators show that inflation has returned to the bank’s 2% target. Britain’s unemployment rate rose to 4.4% in April, the highest level since September 2021, with 1.5m people looking for a job but unable to find one. Industrial output and construction activity also dropped, adding to the rate-cut argument.

Consumer prices in China rose 0.3% year-on-year in May, below economists’ forecasts. That marked the fourth consecutive month of consumer price inflation; however, food prices continue to fall. Despite this, the Chinese economy is growing. Retail sales climbed 3.7% for the year to May—the 16th consecutive month of growth.

The Reserve Bank of Australia also didn’t change interest rates. They decided to leave them at 4.35% during their June meeting—rates haven’t moved since November last year. The bank warned that inflation is stuck above their 2-3% target range. However, recent data shows that GDP and wage growth are falling, unemployment is rising, and the country is in a real per-person recession.

Japan’s annual inflation rate rose to 2.8% in May 2024 from 2.5% in April. This increase was driven by a sharp rise in electricity prices as energy subsidies ended, reversing declines over the past 15 months. ■

Books | Learn stock valuation

How To Value Stocks

A practical guide to figuring out what a company is worth

This book will teach you how to value any public company. People think valuation is complicated, and that you need giant spreadsheets of data to do it. But they’re wrong. This handbook is written in plain English, and will equip you with the skills you need to calculate any stock’s fair value. You will be taken step-by-step through the entire valuation process and gain a solid foundation for making better investment decisions.

This book will gradually build your understanding—each chapter expands on the previous one. It will lead you from not knowing anything about valuation to having a deep understanding. It is also packed with fascinating real-world examples to illustrate key points. This book is for you whether you know nothing about valuation or are an experienced investor looking to improve your skills. All you need is the desire to learn.

Leader | The NVIDIA bubble

Artificial or intelligent?

NVIDIA investors are probably making the same mistake Cisco investors did in 1999. Here’s why.

NVIDIA, the computer chip maker, is now the most valuable public company in the world. This week, the firm's market capitalisation blew past $3.3trn to overtake Microsoft. The company's fans treat the founder and boss, Jensen Huang, like a rockstar. He's been hosting parties with the interns, showing off his tattoos, and signing women's breasts.

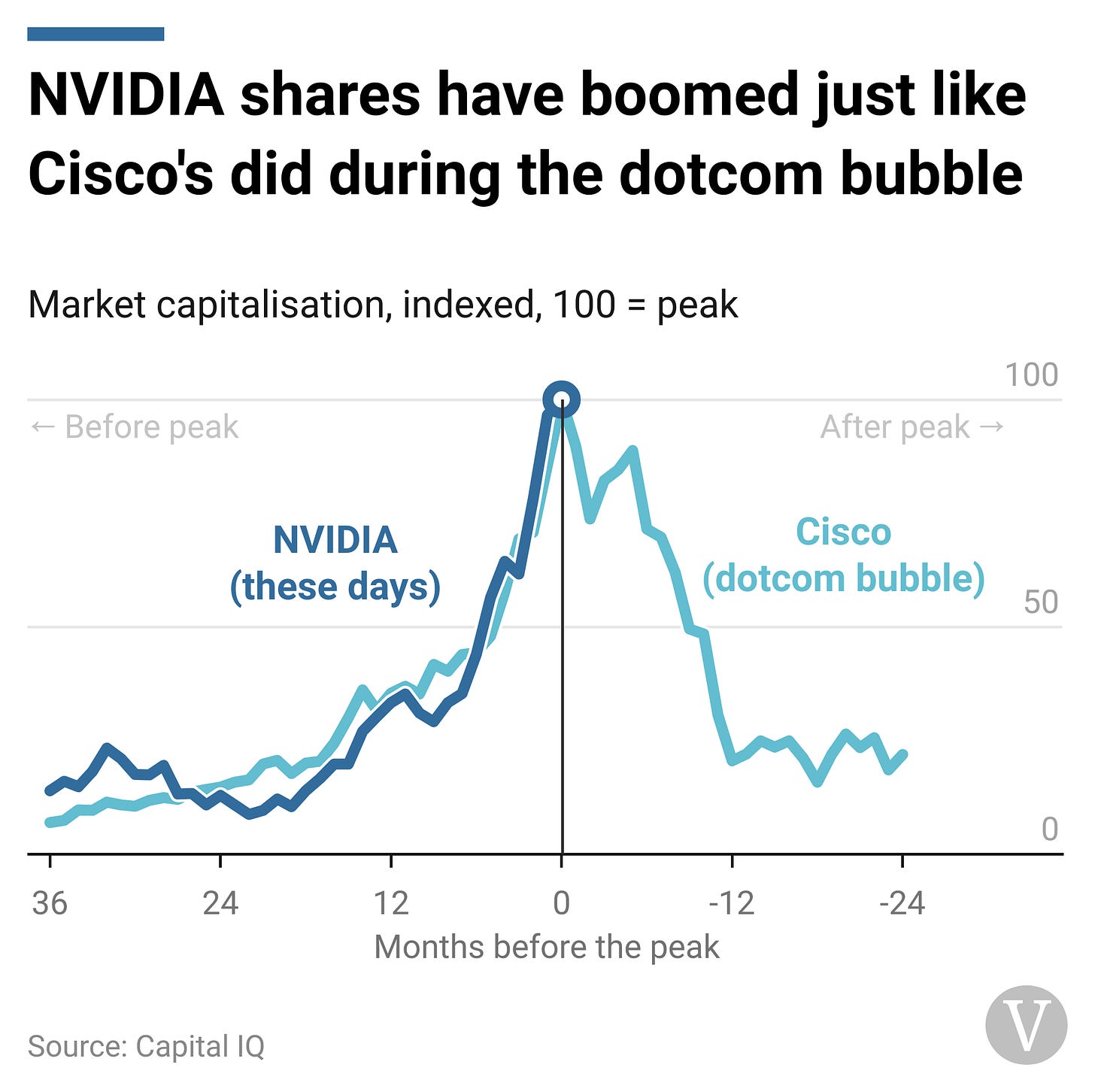

But some pundits, including this publication, are sceptical of the firm's value. The current NVIDIA spectacle is reminiscent of Cisco stock's boom and bust during the dotcom bubble. In March 2000, Cisco overtook Microsoft for the top spot, just like NVIDIA has done now. So, is NVIDIA a bubble, as Cisco was? Probably. Like Cisco before, NVIDIA has gone through the three stages of bubble building. And the rest of the story will likely play out similarly.

The first stage of a bubble forming is when a fundamental shift causes the market to take off. In the late 1990s, the internet went mainstream, and people were excited about its potential. Cisco Systems was a critical networking hardware and software provider whose products powered the web. The company didn't use the internet to make businesses; instead, it provided the routers and switches necessary for the internet to run. As the adage goes, "Sell shovels, don't dig for gold." And that was the mantra many Cisco investors swore by during the boom. Companies needed Cisco's technology to build their networks, so sales flowed. The firm's top line grew at a 56% compound annual rate from 1994 to 1999. Investors and the firm's customers believe Ciscos was indispensable and unstoppable.

Then, as now, a technological shift happened. Nowadays, companies are rolling out artificial intelligence (AI) bots as fast as possible. They need vast computing power to train and run them, and NVIDIA supplies the necessary chips. Sales have boomed—they're growing at a similar pace to what Cisco's did back then. Companies that don't embrace AI will get crushed by it. And, as it was with Cisco, investors are reassuring themselves by chanting, "Sell shovels, don't dig for gold."

All bubbles are built on a core truth. Something changes in how we do things, and our collective imaginations get the better of us. Then, we lean on that core truth to justify evermore ludicrous behaviour. Cisco investors saw that the internet would change the world, just as NVIDIA investors see that AI will, too. The foundation for the bubble has been set.

The second stage is that the pricing mechanism becomes a positive feedback loop. People buy because they expect the price to rise, and that buying causes the price to rise. Investors piled into Cisco shares as the price rose because they expected further rises. Like Cisco's shares did back then, NVIDIA's stock price has grown exponentially. Many individual investors have become afraid of missing out on owning a piece of the next big thing, so they have bought the shares and profited so far. Many of these investors are not buying because they believe the fundamentals justify the price; rather, they expect the price will continue to rise. And they've been right so far.

Professional investors have also piled into the stock. The pressure to perform is overwhelming. It's hard to justify to your investors why you don't own NVIDIA when the share price keeps increasing. Few investors have bet against the shares. Investors have shorted just 1% of the outstanding shares, meaning traders don't expect the price to drop soon.

Markets usually operate with a negative feedback loop—investors sell when the price rises too much or buy when it falls too much. This mechanism dampens price movements and helps prevent them from becoming too dislodged from fundamentals. Would you buy the entire Apple Inc company for $1m? Of course. It's worth much more than that. You'd bid the price higher until it reached about what you thought it was worth. But when the pricing mechanism becomes a positive feedback loop, people buy because they reckon the price will continue to rise, and they'll be able to sell to someone else at a higher price. That buying makes the price rise, which makes them expect further rises. With this, the price begins to dislodge from the fundamentals, and investors bend their forecasts to fit the new narrative. The bubble is building.

The third stage is that investors bake improbable expectations into the price. They see the price rising and force their assumptions into that picture instead of the reverse. At the stock's peak in March 2000, Cisco traded at an enterprise value-to-sales multiple of 35x—mind-numbingly high. For perspective, if the company didn't have any expenses and paid out all profits to shareholders and lenders, it would take 35 years for those investors to recoup their investment. They expected growth wouldn't slow and the firm would eventually spew cash. But the reality of a competitive marketplace meant competitors popped up, growth slowed, and profits could never reach the lofty heights required to justify the price. The stock tanked. Similarly, NVIDIA's enterprise value is 42x the firm's revenues—an even higher multiples than Cisco's peak.

That valuation suggests investors reckon NVIDIA will enjoy a multi-decade run of undisturbed explosive growth—an improbable, if not impossible, outcome. Further, it means investors think the firm will eventually produce industry-leading margins and face little competition for its silicon chips. Again, this is a tall order. Either assumption on its own is unlikely and should make investors pause. But combined, it becomes even more unlikely. The final stage of the bubble is set. Any little pinprick could pop it from here. ■

Letters to the editor

A spicy disagreement

I must disagree with your analysis of Guzman Y Gomez’s IPO (“Buying Guzman’s shares is nacho best idea” Vol. 4, No. 12). You argued that the shares were overpriced at A$22, but the market clearly thought otherwise. On their first trading day, Guzman’s shares jumped to A$30. This impressive rise indicates strong market confidence and contradicts your analysis. I’m glad I ignored you and bought.

— Daniel Price, Melbourne

Putting the human in computers

I loved your article on AI (“Discovering our humanity” Vol. 4, No. 12) and its impact on our lives. Some people are scared AI will take away jobs, but honestly, it’s going to make things so much better. AI will boost productivity and let us focus on the more creative and meaningful work. Your comparison to the internet boom was spot on. It’s exciting to think about all the repetitive tasks AI can take over, freeing us up for more interesting and human-centered work. Thanks for showing the positive side of AI. It’s refreshing to see some optimism!

— Alex Johnson, San Francisco

Dilution salutations, in response to (“Dilutaphobia” Vol. 4, No. 11)

“Dilutaphobia”? I’m old enough to remember the tens of thousands of companies that have destroyed investors by diluting. You want to call that an irrational fear? Go ahead. As a proud dilutaphobe, I believe you’re doing a disservice to investors by urging them to disregard a key red flag.

— Tom Patterson, Chicago

Reply directly to this email or send your commentary, critiques, and rebuttals to valuabl@substack.com. You can also direct message ValuablOfficial on X. Please include your name and city. Letters may be edited for brevity.

Finance | Chinese stocks offer value and growth

Made in China

China looks like a good hunting ground for value-oriented investors. Here’s why.

It’s been a tough few years for investors in Chinese stocks. The Shanghai Composite Index of Chinese companies has gone precisely nowhere. It was at 3,000 five years ago and settled there again yesterday. But Chinese companies and the economy have grown. China pumps out almost a third more stuff than it did five years ago—their gross domestic product has risen 30% since the start of 2019. And their companies have access to vast amounts of cheap Russian oil. That’s helped profits. Aggregate corporate after-tax profits have risen 50% in that time. That raises the question: is now the right time to buy Chinese stocks? Yes. China looks like a good hunting ground for value investors.